Instrumental Music in Decline: Where Have Instrumentals Gone?

Instrumental music has been increasingly unpopular in recent decades. Billy Brooks provides his in-depth analysis on the topic and presents his viewpoint on why this is the case.

Musical culture in the West has changed a great deal over the last few decades, and one of the most notable pivots is the decline of instrumental music, which has been largely replaced by songs with lyrics. Much of this change can be attributed to shifts in the popularity of various genres, and what cannot be attributed to that, is probably due to changing levels of musical competence, and the technologies that enable people to play and access music themselves.

Looking at which genres were most popular in America in 2018, according to streams and sales, there are no surprises: hip-hop, rap, pop, rock, and R&B were the most popular, in that order, accounting for a combined 66% of the market.

Meanwhile, it is very noticeable that genres which have historically placed a heavier emphasis on instrumental performances are deeply unpopular. Electric Dance Music (EDM) is the most popular of these genres capturing just 3.9% of the market, while World, Jazz, and Classical combine to account for 3.6%.

Of course, jazz and classical include a mixture of instrumental and vocal music, but it is a much more balanced mix than in almost any other genre. Listening to Ella Fitzgerald, or perhaps a Mozart requiem, or a Verdi opera, you can hear talented singers, but for every Ella, there’s a Davis and a Coltrane, and for every Magic Flute, there are several instrumental symphonies.

There is also a tendency in modern genres well into the nineties to mix the two, which often happens in jazz. Popular rock musicians such as Jimi Hendrix or Eric Clapton, and later, prog acts especially, would combine extended instrumental solos with vocals in order to add interest and structural variety to their songs.

One of the interesting things about the unpopularity of these instrumental genres is the comparative sophistication, perceived or actual, of the less popular categories. Speaking about EDM, Henry Rollins once memorably remarked that he was unsure which came first, the bad music or the drugs. By comparison, jazz and classical music are perhaps the two genres which most actively encourage mastery of individual instruments, and which are inescapable for serious students of music performance and composition.

While there are certain sub-genres of rock, such as heavy metal, which have rewarded virtuosic musicians with respect and popularity, there are others, such as punk, where playing capably is either not that important, or frowned upon. This polarisation is impossible to imagine among jazz and classical musicians, who only accept talented musicians as their peers.

One of the reasons for this might be that there is something more innate and accessible about a performer using their voice than playing an instrument. Everybody can sing – perhaps not well, but to sing at all takes no training, whereas even comparatively simple instruments, such as the ukulele or the ocarina, require a small amount of training to master the basics.

A similar dynamic is present in the difference between speaking and writing; kids master the power to complete full sentences in their native language without any practice, whereas writing takes hours of tuition every day for years.

This gives vocalists the power to express themselves with very limited training, which could allow them to show off other capabilities more fully. Take Bob Dylan for example. He is no virtuoso on any instrument, and the quality of his singing is polarising, to say the least, but singing allows him to show off his incredible talent for songwriting and lyricism.

Democratising performance in this way is probably down to changes in music technology since the turn of the 20th century, which in turn impacted the ability for musicians to perform.

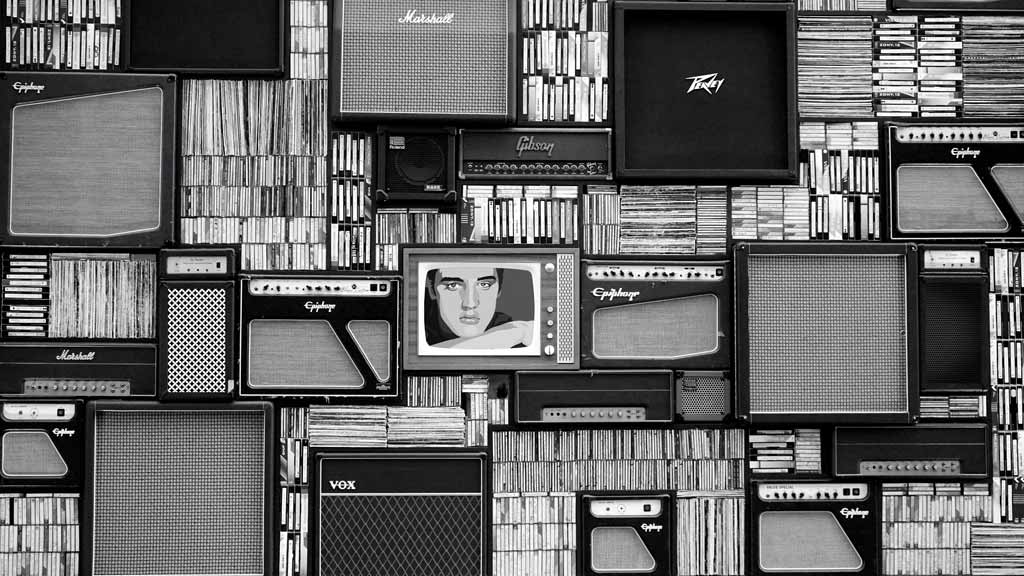

The invention of the pickup, the microphone, and the portable amplifier all allowed instruments which had previously not been particularly popular to flourish. Before that, the instruments which were used in large scale performances most frequently (piano, violin, trumpet) were naturally loud, whereas an acoustic guitar was never even included in most orchestras, as it was simply inaudible.

Making instruments such as the electric guitar, the electric bass, and (with a microphone) the voice much louder, enabled those who used them to entertain large audiences. They are also easy instruments to combine – playing a piano or an amplified guitar while singing into a microphone means that single performers can entertain large groups with few resources.

Meanwhile, one cannot easily combine vocals with a classical stringed instrument, and cannot possibly combine wind and vocals. This technological advance meant that performers of sung blues, jazz, rock, and eventually early R&B, funk, and soul had acts that were easier to monetise.

Technological advancements have plainly driven the popularity of much newer genres as well: there is no electro music, disco, hip-hop, or EDM without significant advances in synthesiser, sampler, mixing, and production technologies.

However, this democratisation of expression means that popular appeal can often be achieved by performers who do not necessarily have any great degree of musical talent.

It would be cruel to include Bob Dylan in that pool, but certain punk bands, and later, EDM producers do not need to exhibit any skill at all at performing with musical instruments in order to achieve their popularity. This is clearly apparent from the famous “now start a band” slogan from the height of the punk days. However, I would argue that this approach has lowered general standards.

Before the punk movement, if somebody picked up a guitar at a party, there was probably a reasonable expectation that they knew what they were doing with it, but no such luck in 2020.

This has enabled many performers such as Lil Wayne, and Taylor Swift, to use instruments (especially the guitar) as props, which further confuses their fans. This is anecdotal, but when I informed a friend of mine from university that Lil Wayne was not as he contended a talented guitarist – in fact I have seen no evidence to suggest he even knows how to play a guitar badly – they were shocked.

This lack of musical calibration and inability to accurately gauge musical talent is a problem for jazz and classical musicians, who trade solely on their ability to play complicated material. A George Benson or a Wayne Krantz is likely to be the most talented guitarist in any room they walked into today, but would the average person know it if they saw it?

This could be due to the seemingly never-ending strangle-hold of neoliberal governments on investment in the arts, and arts education. In the UK, music education has been privatised almost out of existence in schools, so that learning an instrument, or being taught music theory, is unlikely to happen within music departments, but requires private tuition.

What’s more, while there are constantly government sponsored ad-campaigns designed to encourage young people to take up STEM subjects, allegedly to increase future private sector dynamism and therefore the students’ employment prospects, arts qualifications are dismissed as a waste of time, money and effort. Thus, arts funding in the UK fell by 3.6% in real terms in the last decade. In reality, arts and culture contribute more to the UK’s economy than does agriculture, and that contribution would only increase with robust funding for education. However, this seems to diminish the contribution to taste of the market, which is ultimately controlled by A&R guys, executives, and marketers.

While in the ‘50s, through to at least the ‘70s, record labels were keen to present as broad and eclectic a range of products as they could for audiences, this tailed off as record companies became more focussed on profit maximisation.

Frank Zappa is one musician who lauded record labels’ willingness to experiment with what could be successful, without which he would not have had a career. But while such experimental musicians were frequently encouraged in his day, music has become more formulaic, often literally.

Increasingly, A&R, who would have visited live shows to scout prospects in days gone by, rely on algorithms to interpret trends on sites such as Bandcamp and SoundCloud, allowing the audience to dictate to the market what music should be successful.

This seems logical: give the people what they want; the customer is always right.

On the other hand, with fewer people exercising expertise and a reduced willingness to take risks with interesting but potentially unpopular acts, popular music has become less varied, and challenging.

Frank Zappa’s son Dweezil frequently insists that, while there’s nothing wrong with Beyonce, for example, it seems to him that the biggest reason for her popularity is that she’s what’s on the radio, and if Frank’s music was still on the radio, he would still be popular too.

For more on this topic, watch out for an upcoming article on the paradox of choice in today’s listening habits.

Billy Brooks is a British journalist and musician.

Data visualisations made with Flourish.

Request a Personalised Demo

Request a Personalised Demo